What started as a teaching tool for blind children quickly became a nationally-acclaimed symbol of literacy and patriotism.

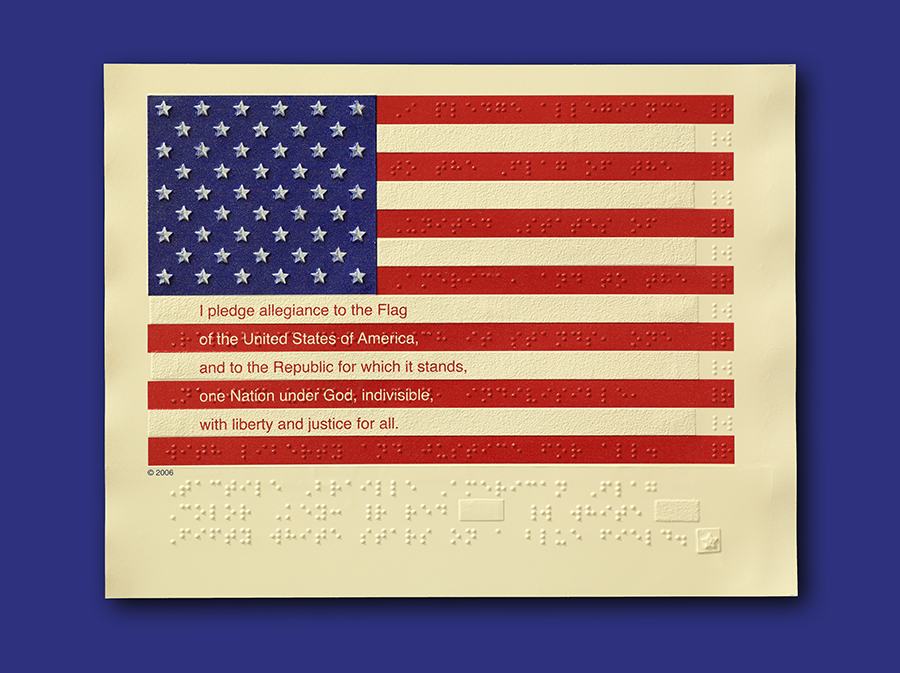

A new version of the American Flag features the Pledge of Allegiance transcribed in Braille on its surface. Those without sight can read the words with their fingertips while also interpreting the embossed stars and stripes. For the first time ever, the star-spangled banner’s iconic beauty is accessible to the blind through touch.

The Kansas Braille Transcription Institute, a nonprofit corporation dedicated to improving Braille literacy, started producing the flags in 2005. Today, bronze versions are on display at Arlington National Cemetery and the National September 11 Memorial and Museum. The flag’s creator, KBTI founder Randolph Cabral, said that he wanted to honor his father, a World War II veteran who lost his sight.

As it turns out, Braille has military roots. A French army captain named Charles Barbier de la Serre invented it in the early nineteenth century. “Night writing” was designed for soldiers to exchange top-secret information without light and without speaking. But the code was difficult to master, and it never took off. Later, a young blind student named Louis Braille realized the potential of Barbier’s invention. He simplified the code to make it easier to interpret.

Braille consists of tiny raised dots on a tactile surface. Different dot configurations represent different letters of the alphabet or, occasionally, groupings of letters. By learning which configurations represent which letters, visually impaired people can put together words.

This relatively new system of communication is already sliding into disuse. The National Federation of the Blind has reported that fewer than 10 percent of 1.3 million blind Americans read Braille. By contrast, in the 1950s more than half of all blind people were learning to read Braille. Since then, the world has been introduced to things such as audiobooks and voice-recognition software. Advocates for Braille literacy believe that it’s still relevant, if not vital, to the blind. They point to studies showing that Braille literacy leads to higher education, better jobs, and stronger independence.

Despite KBTI’s well-deserved acclaim for creating the first Braille flag, the institute remains focused on increasing Braille literacy through its transcription services. From bank statements to textbooks to church hymnals, KBTI interprets everyday things that much of the sighted world takes for granted.

The Braille American Flag costs only five dollars, a small price for such a unique work of art. If you decide to purchase one, consider adding a donation to support literacy for the blind.

To order a Braille American Flag or learn more about transcription services for visually impaired people, visit KBTI.org or call 265.9692.